Carter keeps hope in battle with brain cancer

When Marc Carter left his office on a Friday afternoon in December, he intended to return the following Monday. Little did the associate professor of psychology know that he would not return for nearly a month.

On Dec. 8, Carter, who also serves as the chair of the Behavioral and Health Sciences Department, was diagnosed with a brain tumor, known as astrocytoma.

Such a sudden and extreme diagnosis came as a surprise, even though many Baker University faculty, staff and students noted changes in his mood and behavior in the weeks prior.

Marc Carter, associate professor of psychology, was diagnosed with a brain tumor, known as astrocytoma, on Dec. 8. He will be on disability leave during the spring semester while he continues treatment, but he plans on returning in the fall “good as new.”

“I knew things were happening, but I don’t think I quite understood it,” Carter said of the lead-up to the diagnosis. “The symptoms were very weird. They were almost perfectly consistent with clinical depression, and that’s what we went to see the doctor about initially.”

Robyn Long, assistant professor of psychology, said she began to notice behavioral differences in mid-to-late October.

“The initial thing that I noticed was that he just seemed down, and when I asked him if he was OK, he did share with me at that time that he’d had some insomnia and respiratory issues,” Long said. “Then we hosted a regional psychology conference at the beginning of November, and in the lead-up to that, he would have conversations with me several times about the same issue, which I knew was really unusual for (Carter), but I still attributed it to some severe fatigue and stress.”

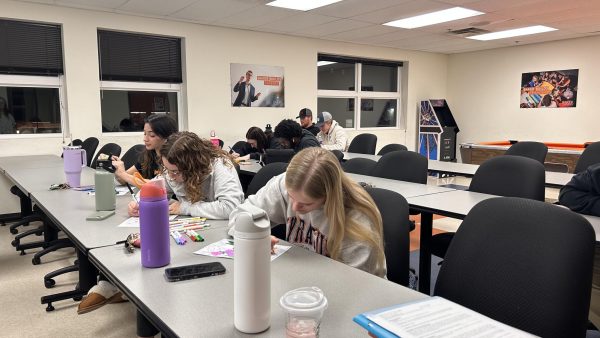

Long was not the only one to notice unusual behavior in Carter. Senior psychology major Tara Chumley was enrolled in Carter’s History and Systems senior-level psychology course along with many other students who were familiar with Carter’s usual teaching practices.

“He wasn’t acting like himself,” Chumley said. “He usually is really upbeat and always comes to class prepared with discussion, but we kind of noticed that flipping toward the end of the semester and could tell that something was wrong because he was a little lethargic and seemed to be in a daze sometimes. And we knew that wasn’t how he usually is.”

After the weeks went on and Carter began being late to his classes, nearly missing them altogether or losing his train of thought during lectures, students and faculty became more concerned.

“I had several students approach me, asking if he was OK, and for a while I did think the combination of fatigue, depression and stress could explain the uncharacteristic behavior, but then I started wondering if there was something organic going on,” Long said.

On Dec. 8, Carter’s wife, Professor of French Erin Joyce, became alarmed when Carter’s speech, posture and balance were markedly affected, coupled with severe headaches.

“Finally it was just like, ‘OK, dude let’s get you to the emergency room,’” Joyce said. “I really thought it was a medication interaction, because he had started taking antibiotics for a sinus infection, and then he was taking drugs for the depression, and then he got some pain medication for the headaches. So, I really just thought it was an imbalance in the medication and they were going to change it and send him home, but that’s not what ended up happening.”

On Dec. 11, Carter underwent surgery to remove the tumor in his brain, and by Dec. 13 he moved to a rehabilitation unit to practice walking and regain coordination.

Joyce said Carter’s recovery after the surgery was remarkable.

“It seemed like every 12 hours he’d be a different person,” Joyce said. “He’s doing really well.”

Carter, who has his Ph.D. from the University of California at Irvine, has understandably approached his situation from an academic’s point of view.

“This is all actually really interesting to me because I’ve been studying brains for about 30 years,” Carter said. “I wanted to see my scans and they didn’t want to show them to me, but I said, ‘No, you don’t understand, I know how to read these. I know what these mean, and I want to see them.’”

Carter was, in fact, in a situation of knowing more about his condition than the average person would.

“He’s a person who has studied, more than other psychologists, the brain,” Long said. “I think more so than some of us that just teach at the intro level, he has more understanding of what’s going on with him and, fortunately, he is somebody that thinks that having more information and knowledge is power.”

While Carter’s prognosis is unknown, the good news is that even though the median survival time is 18 months, a treatment was discovered in 2006 that has proven to be very effective.

Carter is currently undergoing a combination of a chemotherapy drug along with radiation and is in a stage III immunotherapy trial in hopes that some of his own white blood cells will attack the cancerous cells and get rid of the ones the surgeon might not have been able to see.

“Physically, I feel fine right now and I’m feeling very confident,” Carter said.

Although Carter’s recovery has been better than he initially could have hoped for, he will still be on disability leave during the spring semester while he continues treatment but plans on returning in the fall “good as new.” Meanwhile, other psychology department faculty, as well as an adjunct professor, absorbed his classes.

“I’m sad for our students that don’t get the experience of having class with him this semester, and I’m sad because he’s just good energy in this hallway,” Long said. “But I’m relieved for my friend and it’s the right choice for him to take the time off.”

In the time off, Carter will continue treatment and hopes to regain some of his short-term memory, which he began losing in the months leading up to the diagnosis.

“I have a memory book, which is a thing that I use, carry with me, and make notes about stuff because I do have trouble remembering things,” Carter said. “So far, though, my biggest problem seems to be remembering to bring the book with me, but when I have it, things go pretty well.”

Overall, Carter said he would describe his experience as a positive one and hopes to use it to address a stigma he thinks society attaches to mental illness.

“While I was going through the early phases of these symptoms, they were almost entirely consistent with something purely psychological and I just thought about how much more credibility I would get from people if I have a giant scar on my head than if I didn’t, and that’s not right,” Carter said. “Just because it’s not organic doesn’t mean that it’s not real.”

While Carter is feeling optimistic in regards to the short term, he knows the terminal cancer will eventually claim his life.

“I want to talk to my medical oncologist about what it’s going to look like at the end, because it’s going to get me, like I said, unless I get hit by a bus or something, but what is that going to mean?” Carter said. “Bad headaches? Seizures? Because I want a party. I want a big-ass party. When it gets close to the end, I want everybody I care about to come over and just hang out … I don’t want people sitting around being sad.”