The Whistleblower and the Watchdog: Why Snowden deserves a pardon

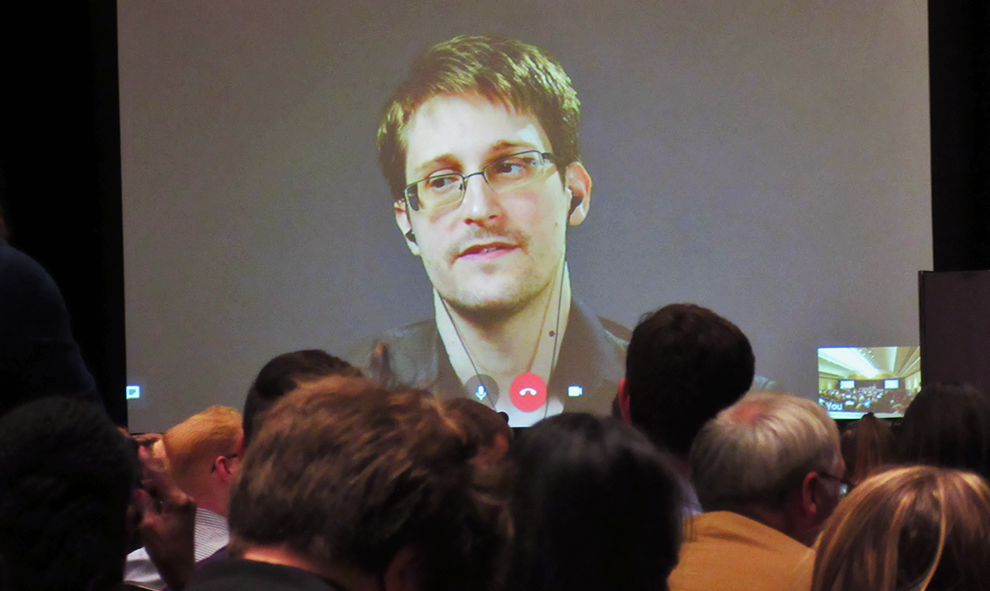

Whistleblower Edward Snowden gives a speech to young aspiring journalists at the Associated Collegiate Press National Conference on Saturday, Oct. 22. in Washington, D.C. Snowden talked about his reasoning behind leaking classified documents to the public, saying he does not regret his actions and would do it again in a heartbeat. Image by Sarah Baker.

Sitting in front of his webcam in a studio in Russia, Edward Snowden gave a speech to a group of young aspiring journalists at the Associated Collegiate Press National Convention on Oct. 22 in Washington, D.C. As Snowden appeared on the screen, all in attendance applauded and cheered loudly at seeing this controversial figure. Future members of the media – the fourth estate of the government – did not hide their awe and admiration.

That speech broke an ACP attendance record for a keynote speaker, and when the forum was open for questions, dozens of students lined up in front of the microphone to have a chance to ask Snowden questions. When his speech concluded, he received a lengthy standing ovation.

It was clear in that setting, among young journalists, Snowden is considered a patriot and a whistleblower. Snowden gave a short laugh and remarked how he is not used to such a positive reception.

The Leak in the Boat

In 2013, Snowden was working for the CIA and had access to classified National Security Agency (NSA) information. Upon learning that the U.S. government was gathering meta-data – such as cell phone records, searches, emails, instant message conversations and various other forms of digital data – belonging to millions of American citizens, Snowden decided this was not a secret that should be kept from the public. He said he tried voicing his concern to higher ups in the NSA and to colleagues, some of whom shared his unease but did not want to draw unwanted attention to themselves.

Snowden eventually leaked classified NSA documents and information to journalists whom he trusted to break the story. He said he felt forced into disclosing his identity when it was apparent that some of his NSA colleagues would be under intense scrutiny until the NSA found the leak.

His disclosure exposed that the U.S. government was monitoring people on a massive scale and that officials were lying about it to Congress. Before this revelation, the idea that the U.S. government was spying on its own citizens was merely stuff of conspiracy theories. Now, post-Snowden, we are much more aware of privacy rights and the ethical debates that come with our technology.

Largely as a result of Snowden’s leaks, in May 2016 a Senate Judiciary Committee met to review the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Amendments Act. The act had allowed for mass surveillance by the government, including data collection without a warrant. The committee report featured four recommendations: limit the scope of surveillance or stop it entirely, require the government to submit surveillance targets for judicial review, prohibit backdoor searches, and mandate transparency and oversight.

Home Away from Home

After Snowden had applied for asylum in more than 20 countries, in August of 2013 Russia agreed to offer him temporary asylum as an international refugee international refugee.

As the situation currently stands, if Snowden attempts to re-enter the United States, he will be charged and convicted under the Espionage Act of 1917. Snowden’s legal representative Jesselyn Radack said in a 2014 Wall Street Journal article that this “arcane World War I law” was meant to prosecute spies, not whistleblowers. She also said that this would prevent him from receiving a fair trial.

“The Espionage Act effectively hinders a person from defending himself before a jury in an open court, as past examples show,” Radack stated, referring to past whistleblower convictions under the Espionage Act: Thomas Drake, John Kiriakou and Chelsea Manning.

The Whistleblower and the Watchdog

The media have always had an interesting relationship with whistleblowers like Snowden. They often go hand-in-hand and share the same goal: keeping the government transparent and pulling secrets out of the shadows. Media are often called the watchdogs and fourth estate of the government, given the authority to keep the government in-check by the Founding Fathers.

When Snowden committed his “treasonous” act of leaking information about the government’s mass surveillance of the American public, he was exposing secrets that citizens needed to know. He was playing his part as a whistleblower, and he let the watchdogs know. The watchdogs are often freer and safer from legal action because they are the press and have the First Amendment in their pockets. The whistleblowers, however, may face more obstacles. They can be convicted under the Espionage Act, like Chelsea Manning, or they are simply fired, silenced or discredited. Are they Tattletales? Martyrs? Disloyal? Heroes? Or Patriots?

It’s time for the pardon

President Obama will leave his two-term presidency Jan. 20, 2017. If Obama chooses to issue Snowden a pardon, he will have to do so within the next three months. Snowden’s pardon is not a likely action for a new president starting his or her first term.

Washington Post and Watergate reporter Bob Woodward, who spoke at the ACP conference the day before Snowden, said that he had been attempting to coax out the reasoning behind President Gerald Ford’s pardoning of Richard Nixon from Ford himself. Eventually, Ford told Woodward that despite the pressure from Nixon’s staff to provide a presidential pardon as part of a deal for Ford becoming president, he only decided to pardon Nixon because he thought it was time for the country to move on. Woodward said Ford did not want the country to re-live Watergate for years – which would have included long court cases, lots of media coverage and the possibility of a former president sent to prison.

This reasoning could, and should, apply to Snowden. If Obama pardoned Snowden, it would be best for the country as a whole. With Snowden absolved of these espionage and theft charges, he could return home and maybe we, as a country, could re-evaluate whistleblowing, government data collection and privacy.

Does the Espionage Act of 1917 need an amendment about whistleblowers? Is it right for the government to spy on the American people without their consent or knowledge? As American citizens, do we even have an inherent right to privacy? Should Americans know every move the government is making?

Furthermore, is it right for our country to charge a man with espionage in connection with mass surveillance? That is a global concern, not just a U.S. issue.

Snowden says that he does not regret his actions. He would do it again tomorrow, and he wishes he could have done it sooner.

“If we only knew what government wants us to know, we wouldn’t know very much at all,” Snowden said at the ACP conference. “We are living through the greatest crisis in computer security history.”