Professor Pumphrey devoted to archaeological digs in Israel

DISCOVERING AKKO

Eight years ago, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies Nicholaus Pumphrey found himself on his first archaeological dig in Megiddo, Israel, while he was studying archaeology and the history of the Hebrew bible at his graduate school, Vanderbilt University. Today, Pumphrey says he is “addicted” to visiting Israel and continuing his archaeological endeavors.

After his time at Vanderbilt, Pumphrey continued his education at Claremont Graduate University. His advisor there was an archaeologist who invited him to dig in the city of Akko, Israel. He has visited that same site every year since.

During Pumphrey’s first dig in Akko, he was made a supervisor of one square because of his experience from his trip to Megiddo. Since then, he said he has “moved up the ranks” to an area supervisor, overseeing five squares of the Tel Akko Project. Pumphrey has also gone from being a student to a professor on the site, and he now gives lectures during his visits.

“As a student you’re just like, ‘Wow, this is fun. I’m digging in the dirt!'” Pumphrey said. “When you become a professor, you’re actually doing research and publishing articles.”

His work in Akko is now more research-based, and he finds himself exploring more than he did as a student. There are Ottoman and Crusader ruins at the Akko site.

“The city itself has the best-preserved Crusader ruins of any city in the world,” Pumphrey said.

The Akko site is also a Phoenician site, Phoenicia means “purple people” because of the purple dye they made from crushed snail shells. Back then, purple was the color of royalty.

POTTERY AND OTHER ANCIENT FINDS

Along with snail shells, Pumphrey has discovered other ancient ruins and interesting artifacts on the site.

“Usually, the coolest thing that you ever find is found by accident,” Pumphrey said.

The most interesting thing Pumphrey has ever helped find while excavating is called a cylinder seal.

“People in the ancient world couldn’t read or write, but they still had to sign their name, so they would wear these seals around their neck,” Pumphrey said. “So when they signed their name, they would slide the seal across the ceramic, which would create an image that was their signature.”

The cylinder seal Pumphrey found created an image of a God standing with lightning bolts in his hands. There are two humans worshiping in front of him and someone in a boat behind him.

Pumphrey also finds pottery on the Akko site.

“We find tons, and tons and tons of pottery,” Pumphrey said. “The first time you’re digging you’re like, ‘Oh, this is something so old, like 2,000 years old,’ and by the time you’re done you’re like, I am tired of all of this pottery because at the end of the day you have to wash all of it.”

Pumphrey said that workers can barely dig and still fill up a bucket of pottery, hence the city of Akko’s nickname, “The City of Pottery.”

Pumphrey has also found numerous bones while excavating, including sheep bones the ancient people used as dice.

“It’s a lot different than just sitting in a library all day long, reading and writing,” Pumphrey said. “So to get out and actually dig in the ground and find artifacts … it’s amazing.”

One purpose of the archaeological digs is to try and find buildings, city walls and whatever is inside the city walls to help recreate the city. At this point, workers at the Akko site might still be far away from discovering those types of ruins, though.

FUTURE DIGS

The site Pumphrey visits is in the seventh year of what was originally supposed to be a 10-year project. Pumphrey himself will be visiting Akko for his seventh time in the summer of 2017.

“I don’t know if we know the site any more than we did on day one, so I think we’re going to be going for a long time,” Pumphrey said. “And if this project ends, I’m just going to look for another one.”

Pennsylvania State University and the University of Haifa (in Israel) are the two main universities that sponsor the Tel Akko Project. The Claremont schools, as well as a few other schools from the United States, also send students and faculty to the site.

Seeking a Baker University connection, Pumphrey and his spouse, Amanda Pumphrey, who teaches Quest classes at Baker, would love to have students come along with them.

Amanda also joined the Akko digs through Claremont University in 2010. She is a supervisor of one square and said she loves the “excitement of the history behind the site” as well as applying what she learns on the site.

“We both started off as students, and now we’re both staff members for the excavation,” she said.

Pumphrey gives lectures while he is there, in addition to training students on the site.

“Instead of just talking about it in a classroom thousands of miles away, we get to go and interact with these people and experience their everyday life,” Pumphrey said.

The Pumphreys have never taken any Baker students, although Pumphrey said he tried to drag senior Anna Hobbs along last year.

“There’s a lot of terrorism over there,” Hobbs yelled with a hint of sarcasm from the other room after overhearing the conversation.

Pumphrey said that is one of the main concerns of students and parents when it comes to traveling to the archaeological sites in Israel. Pumphrey himself has never had any experiences with terrorism or any sort of violence, though, even while a war was going on in the area.

“People are deathly afraid to go, but it’s really not bad,” he said. “In fact, the airport there was voted one of the safest airports in the world.”

Pumphrey encourages Baker students to go, comparing the price to that of an interterm course. He believes that is isn’t that much more expensive than an interterm, but it is “worth more because you get an entire month instead of 10 days.”

“We [Baker] send students all over the world, but it’s only a chance of a lifetime to go excavate ruins and things that are thousands of years old,” Pumphrey said. “That doesn’t happen every day.”

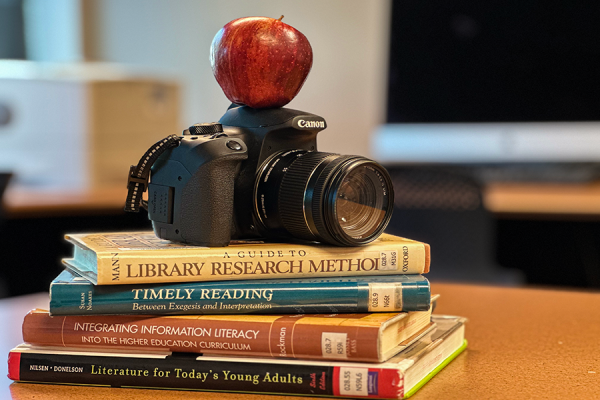

Pumphrey’s courses back at Baker are heavily influenced by his experiences in Israel. His interterm course comes from the same course he teaches while in Israel, and some of Pumphrey’s religtion classes include content that he has learned and discovered in Akko. Therefore, the course changes every year based on his most recent summer experiences.

“I’m constantly learning as I go,” Pumphrey said.

LIFE ON THE MEDITERRANEAN

The digs typically last a month, usually in the month of July. In order to arrange extra sightseeing, Pumphrey often goes early or stays later than the set month. This past year he spent his extra time bird watching.

One of Pumphrey’s favorite parts of his trips is the food.

“It’s on the Mediterranean coast, so the fish is great,” he said.

Popular items served in the area include hummus, falafels, and of course, fish. Pumphrey describes deep-fried seaweed-wrapped salmon and wasabi sorbet topped fish as a couple of weird yet “delicious” foods he has enjoyed while in Israel.

Pumphrey also enjoys taking hundreds of pictures every year during his trips. He said that he has probably accumulated thousands over the past eight years. The number of photos will continue to increase as he keeps going back to fuel his Akko addiction.

“It’s amazing. It truly is,” Pumphrey said. “It’s an experience that will change your life.”