Comparing the Influenza and COVID-19 pandemics on Baker University’s campus

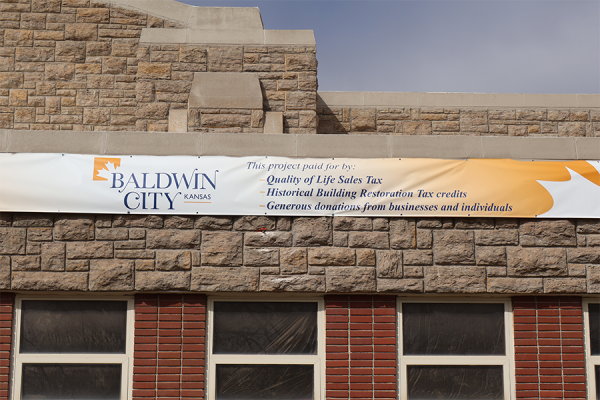

While attending college during a pandemic isn’t a common occurrence, it is not the first time that Baker University has been caught in the middle of one. Just over one hundred years ago, Baker University staff and students had to cope with the rise of an influenza pandemic.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 was caused by the H1N1 strain of the flu virus. Similarly to COVID-19, the “Spanish Flu” was a respiratory disease and caused fluid build-up in the lungs. While the coronavirus’ most susceptible age demographic is the elderly, the influenza outbreak targeted younger populations.

Baker University’s Dean of the Arts and Sciences Darcy Russell is also a virologist, which has allowed her to weigh in on important safety issues on campus and compare them to the events that took place during the influenza outbreak.

“Influenza’s greatest impact was on 20 to 30-year-olds,” Russell said. “This disease killed very fast, sometimes even within a day or two. Lots of young adults and the workforce were dying of influenza back in 1918.”

Hunter Roberts, a senior history and psychology major, has been researching the 1918 pandemic on Baker University’s campus as a part of his senior seminar project.

“The people who were on campus were mostly military soldiers because the campus, in 1917, could act as a military training facility if need be,” Roberts said. “In the fall of 1918, they received recognition as an SATC, which stands for ‘student army training corps.’ They allowed the army to use universities like Baker and KU to use their facilities and staff to recruit army soldiers and officers from the universities.”

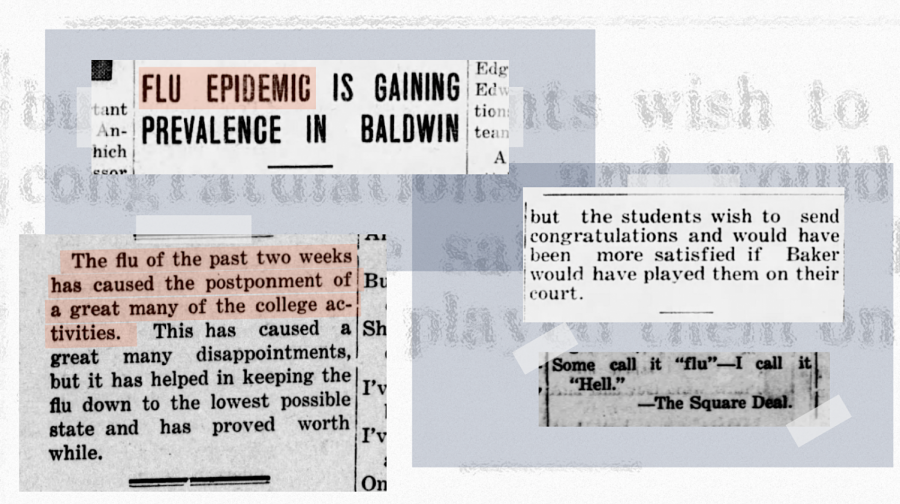

To get a clearer perspective on how the pandemic directly affected Baker, Roberts’ research has relied on the Kansas Historical Society’s database of digitized newspapers, as well as documents stored in the university’s archives.

Sara DeCaro, Baker University archivist and museum director, explained that the state of Kansas experienced around 2,000 influenza cases that mostly began in military areas.

“World War I was going on at the time, and that’s what spread it. You had these young men getting sick and being moved around, and that’s what spread the flu around,” DeCaro said.

Studying the historical documents of the time period sheds light on how drastic the differences were between the current pandemic and the one endured throughout 1918. One of the discoveries that Roberts made was where students were sent if they contracted the flu.

“They opened up the Kappa Sigma and Delta Tau Delta fraternity houses for the patients,” Roberts said. “The Kappa Sigma house was actually used for patients suffering from influenza so they would be able to be treated there. They would recover in the Delta Tau Delta house and then they would go back to campus.”

Despite the difference of just over a century, there are still similarities between the two pandemics. DeCaro noted that in the 1919 edition of “The Yank,” one of the yearbooks collected in the campus archives, one of the students had described their experiences of living on campus during the pandemic.

“Quite a fair section of the male students got sick and it sounds like the girls mostly went home. But we know some of them stayed because [students] wrote about the quarantine,” DeCaro said. DeCaro read part of a writer’s narration of the time period, stating “‘We’re still under quarantine. It’s a real treat to see somebody beside your fellow sufferers. Once and awhile, the girls will slip us pies and sandwiches and talk to us from across the street.’”

According to DeCaro, most of the university’s documentation of the influenza outbreak is from the perspective of faculty members rather than students. By having this perspective from the past, DeCaro has a better idea of what information she wants to collect from the present day.

“We’re definitely focusing on student experiences and individual experiences more in a way that people didn’t back then,” DeCaro said. “But one thing I’m trying to do is collect more from students because I think their perspective is valuable and it sometimes tells you things you don’t get from a top-down perspective.”

Though the influenza pandemic has long since passed, there is value in being able to look back on history and see glimpses of what life had been like during that time. A century from now, documents from the influenza pandemic will still be there for students to examine, as well as the history we are documenting now.

Maria Gutierrez is a senior from Salina, Kan. She is a mass media major and a part of the Alpha Chi Omega sorority. In her spare time, she enjoys writing,...

Zach Reeder is a senior Mass Media major. He plays baseball and has a passion for writing and broadcasting sports. His hobbies include fishing and golfing....