Listen, Believe, Care: Baker tackles sexual assault

May 10, 2021

April marks Sexual Assault Awareness Month, or SAAM, a time dedicated to raising awareness for and preventing the issue of sexual assault, harassment and abuse. In light of this, Baker Rallies Against Violence (BRAVE) organized a series of events to recognize this month and the topics it addressed, focusing on the theme of “Listen, Care, Believe.” These events included tabling, Empower, a self care seminar hosted by the Sexual Trauma and Abuse Care Center (or STAAC) and a meditation lunch.

Empower and Meditation Lunch: BRAVE promotes self care

The first of these events was Empower, which occurred in McKibbins Recital Hall at 7:00 p.m. on Tuesday, Apr. 20. The event was led by AJ Gonzales, a support group advocate from the STAAC in Lawrence, and focused on self care strategies. Gonzales employed a metaphor for self care that surrounded the idea of boba, with ice, tea and bubbles representing the various facets of life which are necessary or which bring joy. Participants then discussed strategies for balancing these parts of life, and were provided with advice in areas ranging from household chores to relationships on how to live a happier life.

Among the attendees of Empower was Sophomore Allie Renfro, who explained that the event helped her in learning to take care of herself.

“I think I was able to think about how I spend my time, and how much time I spend doing the things I have to do, and how much time I spend doing the things that I want to do. And so, going forward, I’ll be able to spend my time the way that I want to and make time to do the things I want to do,” Renfro stated.

The event also offered information on the STAAC and the services it provides, which include free therapy, free support groups, advocacy and a 24/7 hotline that are all available for survivors of sexual assault. Rachel Gadd-Nelson, the PACE project coordinator for Baker University, stated at the event that the school was working to have a campus advocate from the STAAC in the fall of 2021, which could potentially be accompanied by campus support groups.

Empower, Gadd-Nelson explained, was originally based upon the success of Domestic Violence Awareness Week, which was run and operated earlier in the school year with Alpha Chi Omega.

“It was just a space for students to talk and validate one another and learn that they aren’t alone,” Gadd-Nelson stated.

The Empower event was modeled on these ideas, and focused on education surrounding wellness and balance, providing a deeper understanding for students on what self care really means.

“What does it actually mean to listen to what you need and figure out what you need? It’s a bit of giving yourself a break but sometimes it requires discipline,” Gadd-Nelson offered, explaining the core message of the event.

The meditation lunch was originally planned to take place at noon on Wednesday, Apr. 21 near the campus grape arbor and was later relocated to Rice Auditorium due to weather concerns. The event was intended to provide a time for attendees to bring their lunch and be guided through meditation exercises. Gadd-Nelson elaborated that the event was planned to encourage people to schedule time into their day for breaks or mindfulness. However, the event was canceled due to low attendance.

What Were You Wearing? looks at survivor stories

SAAM was also recognized on campus through the week-long installation of the What Were You Wearing? exhibit in the Holt-Russell gallery, which was available Apr. 26-30. The exhibit featured stories from sexual assault survivors beside the clothes those survivors were wearing at the time of their assault. The display aimed to challenge the myth of victim blaming.

“Clothes don’t invite that kind of violence,” Gadd-Nelson stated.

What Were You Wearing? and the stories featured was an idea originally created and compiled by the University of Arkansas in 2013. The gallery has been run in previous years at Baker. However, Gadd-Nelson, who is supervising the project for the first time this year, noted that the exhibit would be somewhat different.

This time, she explained, BRAVE had been able to receive funding from Student Senate, which allowed the organization to buy supplies and make further promotional materials for the gallery. These funds were used to purchase clothing and create high quality signs, which Gadd-Nelson stated were key in making the gallery look “really polished and really well thought out.”

To create the gallery, BRAVE first collected stories from installation resources provided by University of Kansas.

“We looked through the stories, trying to figure out which ones would resonate most with folks here at Baker,” Gadd-Nelson stated.

With stories selected, the organization then set out to find clothing to use for the exhibit. Clothing featured was drawn from previous iterations of the event, as well as Goodwill and from the school theatre department with the help of Assistant Professor of Theatre Emily Kasprzak.

“We just really wanted to make sure that every outfit, every story, was really thoughtful and really intentional,” Gadd-Nelson said.

After stories and appropriate clothing were lined up, outfits were laid out, double checked and adjusted as needed. In the week before the opening of the exhibit, the outfits were set up in the gallery with the assistance of Assistant Professor of Art Russell Horton.

Gadd-Nelson also credited her intern, Belinda Flores, as an integral help in the creation of What Were You Wearing?

With the gallery, BRAVE aimed to bring awareness to the experiences of sexual assault survivors and thus foster education and discussion on the topic.

“Our goal with the installation is to share survivor stories. I think that’s a powerful way for us to learn about sexual assault, to hear it from people who have experienced it,” Gadd-Nelson stated. “It was just such a striking visual, and we wanted to give this as an opportunity to allow people to reflect on survivors’ experiences.”

The exhibit features a myriad of these stories, spanning a wide range of demographics and experiences. In turn, the gallery was intended to provide a space for appropriate reaction to these accounts, whether it be grief, validation or pride in the strength of survivors.

“We just wanted to create that space to engage in those stories, and just really focus on the importance of believing survivors,” Gadd-Nelson explained. “I think people could probably have all kinds of different feelings when they see this exhibit. I think that it could bring up feelings of sadness, anger or grief. I don’t think there’s a right or wrong way to react to it.”

As a display that touches deeply on sensitive subjects, the exhibit is one that indeed is liable to stir up emotional reaction for many.

“We have seen a lot of people commenting on the fact that we have children’s clothing in the story. And I think that has really struck some people, that they maybe didn’t anticipate the story to include children’s experiences,” Gadd-Nelson highlighted.

Ultimately, however, it is the reaction to the gallery that allows it to achieve its purpose, both in encouraging change and providing support for survivors.

“I would hope people see this and feel moved to make a difference in our community. For people that have experienced sexual assault, I would hope they would walk away from this exhibit with a sense of community and not feeling alone, that this is something that unfortunately happens to a lot of people in our community,” Gadd-Nelson stated.

Among the sets of clothes in What Were You Wearing were a couple that featured Baker University sweatshirts. These, Gadd-Nelson clarified, are derived from the original stories gathered by the University of Arkansas and not representative of Baker student stories. The accounts, she stated, describe a generic university tee shirt in their description, and many universities include their own school sweatshirt for the display.

“I think that’s to get to get people thinking about these stories that absolutely can and have happened here at Baker and in Baldwin City,” Gadd-Nelson clarified.

However, while the current exhibition features stories from across the nation, Gadd-Nelson explained that future years may be able to feature Baker-specific stories. To achieve this, the gallery features an option where students can provide their own experiences to be used in coming years.

To anonymously and confidentially submit their story, students were able to either write it out on a slip of paper to be placed in a locked dropbox or use a QR code to access an online link. The lockbox (and the submissions it contained), was then collected at the end of the week to be stored securely in Gadd-Nelson’s office.

“Next year we can really start to expand and deepen the meaning of the gallery by talking about Baker-specific stories,” Gadd-Nelson offered.

The importance of Sexual Assault Awareness Month

Though BRAVE operates Sexual Assault Awareness Month, it also serves a larger role in the Baker community. Among the members of BRAVE is Sophomore Micayla Houser, who serves as the secretary of the organization. Houser elaborated on the overarching role of BRAVE on campus.

“BRAVE is an organization that strives to dismantle all forms of injustice, such as white supremacy and rape culture. They’re all intersectional and all contribute to various forms of violence, including domestic violence and sexual assault. We’re here to create space for conversation and support those who need to be heard,” Houser said.

Overall, SAAM was planned in conjunction with PACE and BRAVE and serves an important role in the Baker community. Houser elaborated on the purpose of the month and its events, stating that “the importance of SAAM lies in the fact that it exists entirely for survivors. It’s a space created specifically for those who have historically been overlooked, and, though the conversation shouldn’t be refined to one month, allows for one specific embodiment of injustice to be fought.”

Gadd-Nelson also offered clarity on the intentions and planning of the month, offering insight into the theme of the month and how it was decided upon.

“This year, we decided that, especially with this past year that we’ve had and how exhausted we’ve seen students to be, we would focus on our theme of Listen, Believe, Care,” Gadd-Nelson explained. “We picked that theme because April is a busy month for a lot of folks, so we wanted to be able to focus on those messages that encourage us to care for others and to care for ourselves.”

Though SAAM provides an opportunity for education and awareness surrounding sexual assault, Gadd-Nelson and Houser stressed that the key to change was that these conversations must be had and that they must occur throughout the year.

“Shying away from uncomfortable or difficult topics of conversation won’t make issues like this go away,” Houser emphasized.

Similarly, Gadd-Nelson expressed that “the biggest thing I’d want someone to actually learn from Sexual Assault Awareness Month is that we can’t just talk about sexual assault during the month of April. It’s something you have to be talking about throughout the year.”

She continued, stating, “I hope people learn that there are people on campus wanting to have this conversation, who want to prevent violence and make a difference, and that there are supports out there for survivors. Here at Baker, we believe survivors. We want survivors to get the care and healing that they deserve. We can work together to create those environments for people.”

The PACE Project and sexual assault education on campus

While the PACE office was a sponsor of SAAM, the office operates in a much broader regard on Baker’s campus in dealing with sexual assault. The PACE Project, or the Prevention, Awareness, and Campus Education office, is based upon a $300,000 federal grant from the Department of Justice provided for prevention and education and response to sexual assault, dating violence, domestic violence and stalking.

“It allows us a lot of resources to work with all different kinds of campus and community partners to look at our policies and make sure they’re working the best that they can,” Gadd-Nelson explained. Partners that the grant allows include local law enforcement and the STAAC.

Dean of Students and Title IX Coordinator Cassy Bailey expanded on the value of the PACE grant.

“Prior to the grant we said we had a commitment to this–we don’t care if it’s a federal regulation and/or not depending on what administration, we’re going to do something about it. We know this is a big problem on campuses, and so we started to do, and continue to do, education, We now just have funding to go with the education initiatives, which is a really big deal,” Bailey said.

The PACE office’s operations on campus include prevention education and victim services. Gadd-Nelson also clarified that, as part of student affairs, she works with student affairs and student life to integrate programming across campus.

“When it comes to sexual assault awareness and education, it can feel like an overwhelming topic, and so it’s my job to make it feel easier to engage in this topic that maybe we’ve been told by society that we’re not supposed to talk about,” Gadd-Nelson stated.

Overall, she offered, the goal of the project is a balance of providing tools to prevent sexual assault and recognizing preexisting sexual assault survivors.

“How do we create an environment where they feel believed and supported? Sometimes what that can look like is letting people know about the different services that are available to students. Sometimes it’s talking about how to support your friend that has experienced sexual assault,” Gadd-Nelson said.

One of the large elements of the PACE Project’s operations is the education it provides to various groups across campus. One such group is BK100 classes, which are mandatory for all freshman. Within this context, the primary focus is consent education.

“Consent is not just about how it applies to our sexual relationships. It’s also about, say, how we hug our friends, and if they don’t want to be hugged we need to respect that. There’re a lot of nonsexual applications to consent conversations. Ultimately, it’s about understanding your boundaries and understanding another person’s boundaries.” Gadd-Nelson explained.

Gadd-Nelson also elaborated that the education includes discussions on complications that arise in such feelings as being nervous or being under the influence. Overall, she explained, the goal of this programming is to encourage students to think about consent in various situations.

“There are lots of different ways that we can incorporate and normalize consent conversations in everyday life,” Gadd-Nelson said.

Another facet of education provided by PACE is that given to Greek life on campus.

“Historically, we have done a lot of education around rape culture and consent culture,” Gadd-Nelson explained. Other topics of education include conversations about healthy relationships and masculinity and how masculinity intersects with violence prevention.

Other groups that receive sexual assault education are athletics, who have discussions on bystander intervention and orientation.

“A student sees one to three presentations. They’re different, but the same message. If nothing else, the importance of that is that the person who is involved understands that this is an important aspect for the university,” Bailey summarized.

Gadd-Nelson also clarified that one of the roles of the PACE coordinator is to examine the policies in place and adjust as necessary. “We’re in the process right now of looking at these different educational opportunities we’ve had on campus and how we can improve them for the future.”

In this process, she expressed a hope for student engagement in identifying what systems are most effective. “There’s a lot of room for creativity and so we’re excited to get to work.”

Beyond policy reexamination, Gadd-Nelson emphasized that there were a variety of venues for interested community members to get involved. These venues include staff and employee training, as well as involvement with Title IX, victim services and more.

“This is a project that’s not just the PACE office. It’s not just me doing all of this. It’s something that we’re partnering with campus and community partners to make this possible, and students are going to be a really crucial part in that,” Gadd-Nelson stated.

One other way students can get involved, she provided, is joining BRAVE.

“The BRAVE student group is a great way for students to get involved and focus on supporting survivors and promoting a culture of consent,” Gadd-Nelson highlighted.

The school also offers a course each interterm that provides education and training for students to become peer leaders. The class features 13 days of education that covers psychological trauma and can help in developing skills that can be used as a peer mentor or as a member of BRAVE.

In multiple facets, the PACE Project encountered setbacks and obstacles in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Gadd-Nelson stated that Greek life education for the school year was hindered by this.

Furthermore, Bailey explained that “COVID put a wrench into the grant nationally for everybody. In fact, last February, right before we were all closed down, a good number of us were in Atlanta for our first training. So we came back ready to change the world and couldn’t because of COVID.”

Title IX: more than athletic equitability

Beyond PACE, the other support structure for victims of sexual assault on campus manifests in the form of Title IX, which stems from the Department of Justice.

“Most people think of Title IX as a women’s athletics equitability, but it’s actually much more,” Baker University Title IX Coordinator and Dean of Students Cassy Bailey stated.

Beyond nondiscrimination, the law also requires a variety of protections and supports surrounding sexual assault. However, Bailey explained, the legal requirements and policies in this area are vastly swayed by presidential administrations and have changed as the administrations have transitioned.

It is through Title IX that the school’s sexual assault reporting system is structured. Bailey said that, through the law, victims have a list of rights for which the school is responsible.

Bailey went on to elaborate on the system by which sexual assault is reported and resolved at Baker.

“Everybody’s a mandated reporter,” Bailey stated. She further highlighted that all faculty and staff at Baker, excluding the counseling center and the university minister, are required to report any knowledge on topics such as sexual assault. “If someone is aware of something, they have to report it to my office, and we do not report that out loud to the group, but we do an investigation and that’s really dependent on what the student wants to do. It’s very victim led.”

Once a report is made, whether by a mandated reporter, a victim coming forward or, as Bailey clarified happens often, a friend of a survivor bringing up concerns, action occurs swiftly.

“When they come into my office, the first thing I can do is listen, believe and offer resources,” Bailey said. Immediate resources available for survivors include no contact orders, the rearrangement of classes, living situations, or even ways that students walk on campus and options in classes that range from late withdrawals to being excused from tests or homework for a period of time. From there, Bailey works with the victim to work toward resolutions.

Students experiencing issues tend to have two options. The first option is an informal resolution, in which a solution is mediated and agreed upon in Bailey’s office.

“They want to have some closure for themselves. They want to make sure the other person is aware of what’s happened,” Bailey explained. “Typically, the victim survivor says ‘this is what I want’ and that’s what happens.”

Bailey went on to describe that in most informal resolution cases, there is a previous relationship between the victim and the accusee.

“Typically, there’s a friendship or knowledge of each other beyond what you see in conduct cases,” Bailey stated. She also explained that, because informal resolutions are agreed upon measures, they are often dependent on the accusee stepping up and admitting what they did was wrong. Overall, Bailey offered, this method can be easier for some victims.

“It changes for the victim because they’re like ‘Thank you–I appreciate somebody saying this, and I don’t need to go through a formal conduct hearing because I got what I wanted, which is you to acknowledge that you hurt me, and so now what I’d like to do is get to a sanctioning period,” Bailey elaborated.

If an agreement cannot be reached, the other available option for resolution arises in the form of a conduct hearing. In this scenario, Bailey becomes solely the investigator for Title IX, and there is no mediation. She begins the process with the collection of evidence, which consists largely of extensive notes and interviews with all involved parties, but can also include elements such as video clips or records of door access.

All of this evidence is then compiled and arranged in a binder, at the end of which is Bailey’s report, which summarizes the elements and conclusions of the investigation. Both victim and alleged perpetrator are able to look over this binder.

In the hearing itself, confidentiality is valued highly. The victim and alleged perpetrator enter through separate exits and are unable to see each other due to a physical barrier. The case is then heard by a trained panel composed of faculty or staff. Each party tells their side, witnesses are brought forward and there is a cross examination.

At the end of the hearing, a verdict is reached and a victim impact statement is read.

“Typically, the person is found responsible,” Bailey stated. Sanctions resulting from a conduct hearing include expulsion, suspension or counseling.

Bailey also clarified that the school’s handling of sexual assault varies from law enforcement in that it operates on a system of preponderance of evidence rather than shadow of doubt, which views it as more likely than not that accusations brought forward are veritable.

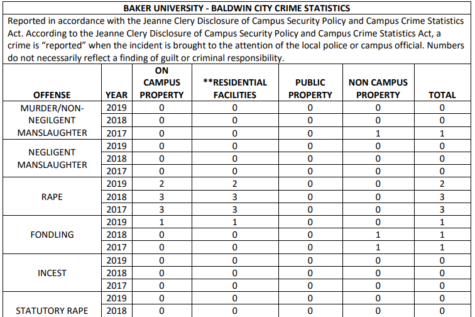

Every time a report is made, it generates what is known as a “Clery number.” This is in reference to the Jeanne Clery Act, a law which mandates transparency from universities in terms of criminal awareness. Under the act, the school publishes an annual security report, which provides insight into the frequency of sexual assault reports at Baker.

Bailey explained that the reports are always a year behind. However, due to COVID complications, the example report below was filed in January rather than October.

Due to this delay, the most recent statistics available from the report are from the 2019 calendar year. However, Bailey was able to provide insight into the number of reports made in the current school year. In the 2020-2021 school year, three reports of sexual assault have been made. There was a fourth report made on Baker University’s Baldwin City campus. However, it was in reference to events that occurred prior to this academic year, and therefore would be counted in the year in which it did happen. Bailey further explained how these were resolved.

“This year it’s been interesting. 100% of them have wanted the informal resolution. We have not done a case,” Bailey said.

She also stated that there were a similar number of reports made in 2020 as a calendar year. But, this framing includes cases that went through hearings.

According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (or RAINN), the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization, approximately one in four undergraduate females experience sexual assault and approximately four out of five cases of sexual assault on college campuses are not reported.

Ultimately, Bailey emphasized, sexual assault is a matter that is not taken lightly by the school.

“Baker takes this incredibly seriously, and so when someone comes forward, maybe that person has already experienced trauma, but what I want them to know is that we’re not going to brush it under the rug. These are not things I’m going to ignore,” Bailey stated.

A survivor speaks out

Sexual assault, however, exists in more than a hypothetical or administrative sense. One student, who has chosen to remain anonymous, shared their experience with the matter. This student offers insight into the reality of sexual assault and reaffirming the importance of listening, caring and believing.

“She was disrespectful of some of my choices. She was disrespectful of my identity. And she just continued to disrespect me, and I think that was just a continued disrespect. She was in an open relationship, and that was cool, but I just wanted to know where we started.

So I asked her, I said, ‘what are your rules? Because I want to make sure I’m not overstepping any bounds within your relationship’ and she was like, ‘well, sex is weird’, and I was like, ‘that’s not a rule.’ You should know whether you’re allowed to sleep with other people or not. I mean in an open relationship, you wouldn’t think that would be a thing you would know and she was like ‘Sometimes it’s okay and sometimes it’s not.’

I asked her, ‘Do you know when it’s okay and when it’s not? Can you help me understand these rules, just because I want to make sure that we’re on the same page. I don’t want to do anything that encourages you to cheat on your girlfriend, and if us making out is cool, then I’m cool, whatever,’ and she just refused to tell me. She kind of kept me in the dark about what our interpersonal relationship was.

It was just a lot. She kept calling me a lesbian, and I was like ‘I don’t identify as a woman, so I don’t identify as lesbian,’ and it was just every category that I identified as in front of her, she was like, ‘that’s so cool that you identify as (thing I don’t actually identify as),’ so it was just this constant dismissal of my self perspective and my ideas and my opinions.

I had gone over to her house that night. She said that she had a mutual friend, and a third person was going back to her house to play video games. And so I agreed to go, because I knew that this mutual friend was going to be there. And I got to the car and I found out that the mutual friend was not in the car. Turns out I knew the third person, so I was okay with it, I got in the car we went to play video games.

She kept trying to kiss me. Even though she had said before, when I had gotten in her car and when we were like texting, she said, just to hang out, just as friends. And she kept trying to kiss me. She kept putting her hand on my leg. And I just, I kept trying to tell her that I wasn’t interested in having a relationship with her if she wasn’t going to be forthcoming with me about the status of our relationship.

And she kept trying to convince me ‘oh, it’s okay. Oh, just kiss me like, oh, it’s not a big deal.’ And she eventually grabbed at my crotch. And when I told her to grab my jacket from across the room she was like, ‘what, what’s the big deal?’ and I was like, ‘I just want my jacket.’ I just wanted another layer of clothing. I wanted, I guess, another layer of protection. Just another layer of armor, so I didn’t feel so vulnerable in that moment, because, you know, even though I was fully clothed I felt very exposed and I just wanted something else. And so eventually I told her to take me home.

She drove me home and she asked to walk me to my door, and I told her I wasn’t comfortable with that. And she leaned over to kiss me and I leaned away from her. And I took her hand off of my waist, and she said something about, ‘I hate that you’re so self conscious, you’re such a beautiful girl you have such a great body.’ Just continually misgendering me, just objectifying me, just all this stuff. And she kept saying let me take you up to your room. Let me. And so I couldn’t figure out how to get away from the conversation. So, I kissed her. And then I opened the door and ran back to my apartment.

Fortunately, some friends were there, a big group of friends, and I said if anyone knocks on the door, one of the men in the room to go to the door and pretend it’s your apartment, and say I don’t live here so I’m not here. Don’t let her know where to find me.

So she called me a bunch of times that night, and I answered her texts to tell her to stop calling me, she left multiple voice messages, multiple texts. I ended up blocking her and she graduated about a month later, and that was really fortunate for me to not have to see her again or have to deal with that.

And if that wasn’t the case I probably would have gone to someone in the Baker administration, but, as it was, it was easier to just live that last month and stay away from her. Because, until a couple months earlier, I’d never met her, never seen her on campus. It was easy enough for me to avoid her because she didn’t know where to find me on campus anyway. She knew I lived in the apartments but that was all she knew.

I’m not gonna say it’s okay, but you know it’s a thing that happened and now it’s over and I feel like I’ve learned stuff from it. You know, there were definitely red flags that I could have paid more attention to, and I wish I would have asserted my boundaries.

It’s hard to categorize things, to, you know, put things on a scale of, like, oh, this was less sexual assault than something else. People try to do that, that’s just not fair. So yeah, it was sexual assault, but I think the biggest issue was that to her the relationship with sexual, and to me it was not.

And so there was just this constant denial of my opinions, and my identity, and that was the biggest thing. I got back to my apartment, and I was crying. I knew one of the people who was there when I got back, and so I really wanted to talk to that person specifically and be like, ‘hey, I need you to empathize with me because I’m feeling really dysphoric right now.’ And that was honestly the biggest thing about it, how dysphoric I was. And it was really unfortunate.

I told the story to someone later, and I mentioned how dysphoric the whole interaction had made me feel, and this person responded with, ‘well, you weren’t dysphoric, you were sexually assaulted.’ And that was also really frustrating, that dismissal of my experience, and them trying to recategorize it.

If someone decides to disclose their experience to you, don’t tell them they did something wrong. And don’t tell them what they should do. I’ve heard so many people say, not about me, but about other people, ‘oh, they should have gone to the police.’ And there isn’t really a universal right way to handle it. And don’t just diminish other people’s experiences.

I guess really it just boils down to let other people qualify their own experiences. Don’t try to tell them that they should be making more or less of a big deal out of it. And don’t tell them how they should respond, because unless you were there in that room, in that body, you don’t know. You don’t know a person’s whole background, and you don’t know how they’re gonna respond to trauma.

And so, even if you’ve had a similar experience, you haven’t had the same experience. I find that it’s not people with similar experiences who try to compare and try to quantify, it’s people who want to make someone else’s experience fit their understanding. And it’s usually an understanding that they have from media.”

If you or someone you know is a survivor of sexual assault, there are a variety of resources available on Baker University’s campus for support.

Reporting resources for survivors include:

o Title IX Reports at Baker University: Dean Bailey (Title IX Coordinator) cassy.bailey@bakeru.edu

o Baldwin City Police Department

Confidential resources for survivors include:

o The Sexual Trauma & Abuse Care Center

o Reverend Kevin Hopkins