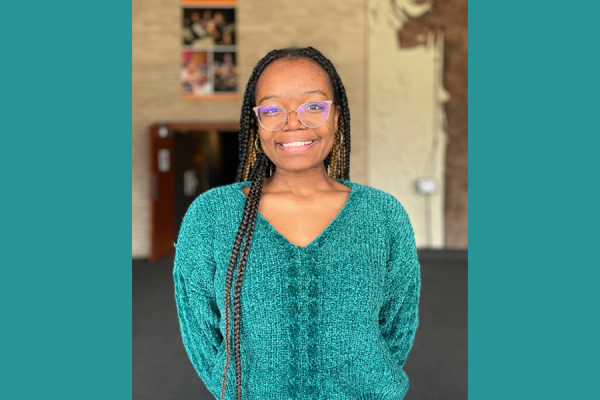

What it is like: The lives and perspectives of Black athletes at Baker University

Junior Tajanique Bell (left), Sophomore Micah Walker (middle) and Freshman Jenica Jackman (right) are three of the many minority student athletes sharing their perspectives on the world of sports at Baker University.

According to the 2020-2021 Baker University Factbook, the Black students made up 9.6 percent of the student population in the 2020 fall semester. Being such a small percentage, Black students on campus often have a different experience than their peers.

For some Black students at Baker, their transitions to college were accompanied by a major culture shock. Leaving their predominately Black neighborhoods and schools to pursue an education in rural Kansas caused them to have to adapt.

Junior Dwight Fagan, who is a running back on the football team, shared his experience of transitioning from his home state of Florida to Baldwin City, Kan.

“I wanted to see what was different. I didn’t want to have any problems or feel out of place,” Fagan said.

Despite existing in a minority group at Baker, Fagan found support from his Black peers which gave him the confidence to face various environmental changes.

“[Coming to Baker] was definitely a major change and I was excited for that, I just had to find ways to overcome those changes,” Fagan said. “At first I wasn’t used to being outnumbered race-wise until I found a few other Black students around here and that helped me settle in.”

Among the overall percentage of Black athletes attending a college or university in the United States, approximately 87 percent of them attend a Predominantly White Institution (PWI), like Baker University, according to Kevin McClain, a research professor at the University of New Orleans.

Junior Tajanique Bell says the transition from the majority-Black Southwestern Community College in South Carolina to Baker was a prominent change for her as a student-athlete. The California native went on to express that her dedication and drive for track and field are amplified simply because of who she is as a Black woman.

“I felt like I had to represent. I had standards and big expectations,” Bell said.

Many of these Black athletes also expressed they have expectations to meet back home. The support of their families often keeps them going, but with it comes the responsibility of carrying on their families’ athletic legacies.

For Bell, maintaining the legacy of generations of athletes within her family is a heavy task.

“As a child in sports, I was told that good wasn’t good enough and that I needed to be great. Once I was great, that wasn’t enough and I needed to be greater,” Bell said.

Bell explained that her upbringing molded her into the athlete she is today, stating that grades were always a priority and her athletic performance was vital to her success at the collegiate level.

“The main goals were to have good grades, be early and not right on time to practice and train as if I were at an actual track meet,” Bell said. “I’ve always had to be an overachiever. I wasn’t allowed to be lazy or procrastinate or to come in any place but first.”

According to Bell, athleticism is extremely valued in the Black community. Since the start of her athletic journey, Bell has been trained to compete for the sake of reputation and representation as a Black woman in her family.

Associate Professor for the University of Miami Othello Harris published a researched book entitled, “The Role of Sport in the Black Community,” discussing the benefits and pressures of athletics in the Black community.

“No longer ignored by collegiate athletic programs, sports franchises fans and the media, African Americans have come to define certain sports and/or positions,” Harris wrote. “Therefore, sport, we are told by some, has opened its doors to African Americans, offering untold direct and indirect opportunities for social mobility.”

Harris explains that there is a value greater in athletics than winning trophies and awards. He says that Black athletes tend to develop a reputation that draws support from their surrounding communities. These athletes take on the responsibility of representing their Blackness and their athletic capabilities not only for more than just themselves.

Being a Black athlete introduces a higher level of standards and expectations for these young athletes, like Bell and Fagan, suggesting that their talents are necessary for putting food on the table. These lessons and teachings from their families have been reinforced in their daily lives at Baker.

Despite the lack in numbers in the Black student body, a community has formed among them. Freshman Zoey Schroeter noticed this bond when she arrived at Baker. In the Cafeteria, Black athletes from different teams gather together to eat with one another, share stories about their days and embrace each other’s company.

Any hesitations Schroeter had soon wore off as she befriended women of color who compete on the cheer team as well.

“I was a little iffy about it at first, but then I saw one or two Black girls on the team and I ended up okay,” Schroeter said.

Freshman Jenica Jackman, another member of the cheer team, agreed about the closeness of Black students on campus.

“As far as the Black community on campus [goes], you can definitely tell that we’ve grouped together. You’ll see us at a table in the Caf or walking with each other to class. You could say we’re like magnets to each other,” Jackman said.

Black American athletes were given a late entry into the world of sports, dating back to the 1940s when American sports became integrated. A Sports Conflict Institute (SCI) article, written by Mitchell Kiefer, states that American sports were not integrated for the first part of the 20th century.

“The National Basketball League officially integrated in 1950. While professional football started with integration from 1900s-1930s (still, the percentage of African-American players was negligible), the National Football League was completely segregated from 1934-1945,” Kiefer writes.

Black American athletes have been in the spotlight for only a small portion of history. Despite the late welcome into the world of sports, athleticism is a well-valued treasure within the Black community. It is utilized to establish an identity and to push past barriers in their paths.

As these students continue to pursue their academic and athletic careers at Baker, they proudly acknowledge their Blackness first and take pride in this greater sense of purpose within their communities.

Colbie is a Senior at Baker. She is majoring in mass media, working towards becoming a photojournalist and is also a member of the women’s track and...