Editorial: Overdose epidemic grows on college campuses

As the overdose epidemic grows on college campuses, it’s important to be aware of the symptoms and realities of drug use.

Before coming to college, we were all told by parents, by teachers, by guest-speakers to say “no” to drugs. It’s a lesson that’s been hammered into our heads for as long as we could remember. But two years into a COVID-19 pandemic, there’s been another epidemic brewing right underneath our noses: an overdose epidemic.

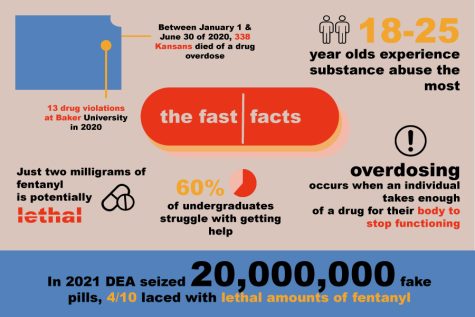

“Overdosing” occurs when an individual takes enough of a drug that it overwhelms their body to the point it can’t function properly. Symptoms vary depending on the drug, but overdosing typically involves chest pain, difficulty breathing, irregular heartbeats and loss of consciousness. Overdosing can be particularly dangerous because sometimes overdosing shares symptoms with regular drug use or the person may be too inebriated to notice what’s going on.

While overdose deaths have been increasing steadily over the past two decades, 2020 has been the highest year with a total of 91,799 recorded deaths in America; over 20,000 more than in 2019. This dramatic jump is equally parts tragic and completely understandable. More Americans began using or increased their drug use to cope with the stresses brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This problem impacts Kansans as well. Between Jan. 1 and June 30 of last year, 338 Kansans died of a drug overdose. To put that into perspective, that is the equivalent of the entire 2020 Baker freshman class.

As college students, we are the group most susceptible to substance abuse. 18- to 25-year-olds are the demographic experiencing substance abuse the most, at 39 percent. During a time of our lives already fraught with changes and uncertainty, it’s no surprise that many would turn to drugs to find some escape in the middle of a pandemic. Even last year, there were 13 drug-related violations right here on Baker’s campus, a slight increase from 2019’s 10 violations.

The most common culprit of these overdoses, both in Kansas and around the country, is a substance known as “fentanyl.” According to the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, fentanyl is “a synthetic opioid that is 80-100 times stronger than morphine.” Opioids are often used as pain medication and cause the patient to feel sleepy, including fentanyl. But fentanyl, both legal and illegal, is commonly added to heroin and other drugs to increase its potency.

Because of how strong fentanyl is, overdoses are especially quick to set in and are much more difficult to reverse than others. Just two milligrams of fentanyl is potentially lethal and there has been a recent influx in counterfeit prescription pills being sold online. The DEA in 2021 seized 20,000,000 fake pills and found that four out of every 10 were laced with lethal amounts of fentanyl. So even a practiced, recreational user may end up overdosing because the pills they took were bad.

Like drinking, it’s common for some college students to turn to drugs as a new coping mechanism to deal with all the pressure they experience at college. Painkillers and opioids like fentanyl are some of the most common substances abused by college students. College students are in a dangerous place and especially susceptible to drug abuse now more than ever.

2020 saw a surge in demand for college counseling services, however, budgets can limit how effectively colleges can provide help. 60% of college undergraduates struggle to get mental health care in the first place. Even when students need help, they may still be hesitant to reach out to get help where it’s offered because of personal doubts and the impact it will have on academics or social stigma.

While there does exist a medicine that can reverse opioid overdoses, efforts are still underway to help make it more available. Furthermore, Kansas is not one of the states that grants immunity to those who call 911 for a potential drug overdose. We could certainly work towards getting such a law passed, but it may be best to start cutting the problem off at its root.

If one of your friends starts showing symptoms of a substance abuse problem, reach out to them with kindness. Help to provide them a safe space to share their troubles and work through possible solutions. If you’re the one using drugs, be cautious of what you’re consuming and find someone you can talk to if you’re worried about yourself.

This pandemic may have isolated us. But to end this overdose epidemic, we need to reach out to each other more than ever and treat each other with compassion.

Student Counseling Center

Dr. Tim Hodges, Director

785-594-8409

Maria Gutierrez is a senior from Salina, Kan. She is a mass media major and a part of the Alpha Chi Omega sorority. In her spare time, she enjoys writing,...

Rebekah Nelson is a senior from Newton, Kans, majoring in mass media and minoring in studio art. She works as the multimedia editor for The Baker Orange...