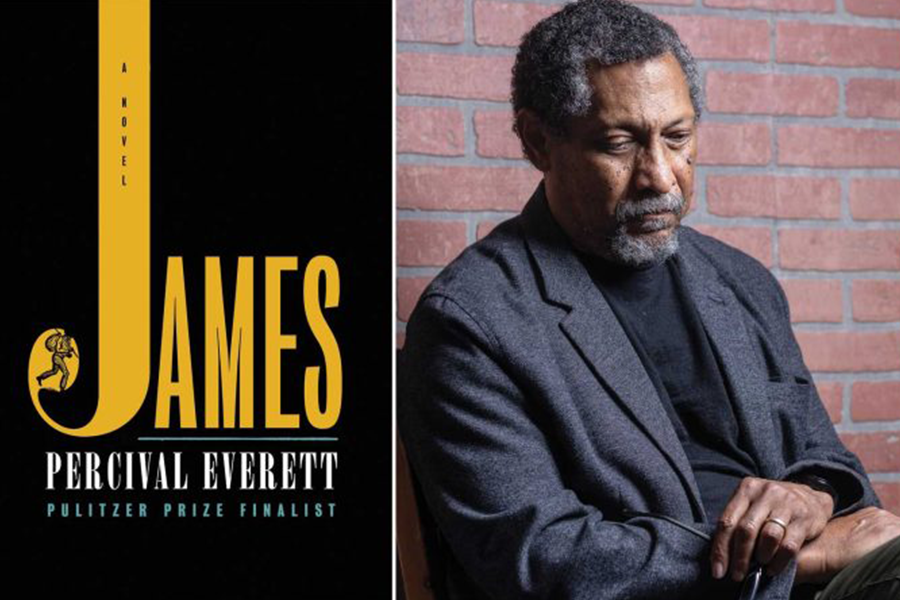

Newly nominated for the 2024 Booker Prize, “James” has proven to be a successful endeavor for Percival Everett, writer of over 30 works of fiction, short stories and poetry since 1983. However, what “James” provides that none of his other works have provided is an Odyssean epic, rewriting (or correcting, depending on how you see it) history.

The novel is told from the first-person perspective of Jim, an enslaved man, who you may remember as Huck Finn’s trusty sidekick in Mark Twain’s “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”. However, little of Twain’s characterization remains; none of ‘Slave Jim’s’ broken English, his neutrality towards slavery nor his stereotypically written stupidity. Instead, Jim is an intelligent, code-switching, empathetic man, evenly balancing his life as the improper speaking ‘property’ and as a thoughtful man who must educate his family and loved ones, lest they suffer unnecessarily at the hands of the plantation owner.

Despite this already reading like a whole heap of fun for our protagonist, Twain sweeps him and his young friend Huck onto the Mississippi River, running towards freedom and away from being sold away from family and an abusive household, respectively. But as we know, freedom is seldom free and has historically cost much more for those outside of the ruling body: in the 19th century, if you were not a man, white, straight, wealthy or educated, ‘running to freedom’ became its own marathon.

Twain’s narrative, a story heralded as the pinnacle of social equality and American literature for decades after its publication, is completely re-contextualized by Everett. While in the original text, Huck happens upon Jim hiding fearfully after hearing he would be sold, “James” follows Jim from his initial reaction to the news, breaking the news to his family and skillfully hiding for weeks prior to Huck even finding him.

Similarly, Twain describes an interaction between Huck and Jim in which they are separated by fog. Once reunited, Huck attempts to convince Jim that he dreamed the whole scenario, to Jim’s complete shock and terror. This same anecdote is described by Everett as it would be in any other case: a boy tries to trick an adult, and the adult feigns surprise.

With “James”, Everett hands autonomy and individuality back to the character of Jim, who, for so long, was nothing but another stereotype of African Americans and an example of a ‘simple’ and ‘good’ black man for the English classes he was taught to.

One of the greatest adaptations I have ever had the good luck to read, “James” is timeless, offering a meditation on freedom and historical reparation, the likes of which readers may never see again.