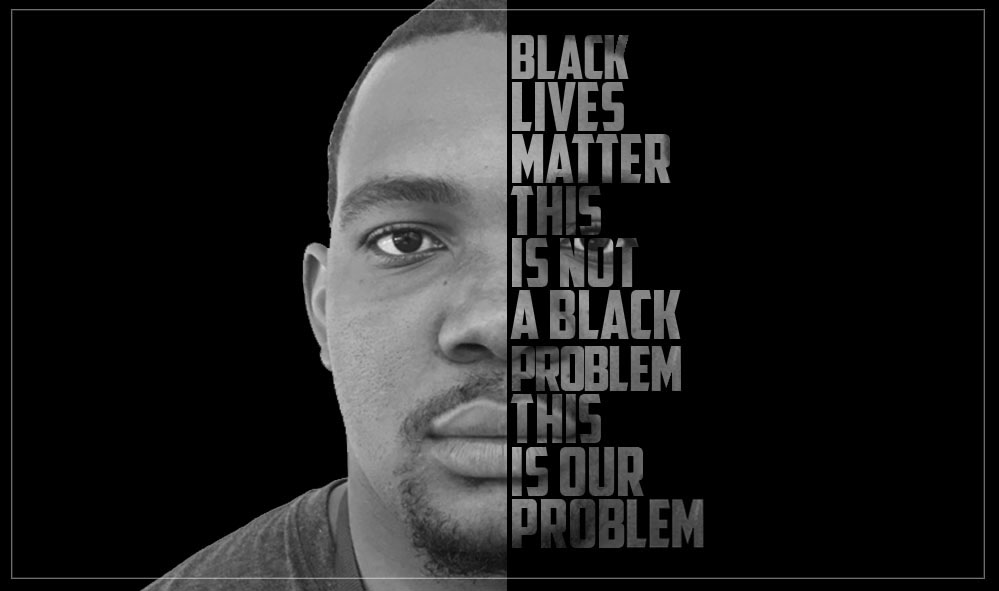

#BLM: face-to-face with racism

August 25, 2016

Three years ago during the Mike Brown investigation, a white man called my then 10-year-old niece a “nigger” while we were shopping at a grocery store. I remember this clearly because I had a difficult time accepting the reality that racism still exists. I knew racial tension was making headlines at that time, but I had never experienced it first-hand.

Racism became real to me that day. It wasn’t one of my grandfather’s stories, a page I read in a history book or something I saw on the news. This was more than my dad telling me he got pulled over for DWB (Driving While Black).

My experience wasn’t much like the cases of Trayvon Martin or Mike Brown, but the hatred I saw that day embodies what I believe led to their deaths. I was face-to-face with racism, and I realized at that moment that I had to stand up for black people, black rights and black culture.

Too many privileged Americans are unwilling to accept that a lot of law enforcement officials and black people have never and may never mutually respect one another. The issue between law enforcement and the black community stems from the 1700s when police officers were called “slave patrol.” They had a responsibility to recover and punish slaves who were the property of white landowners. Take a look back at the Civil Rights Movement, including Rodney King and the LA Riots, listen to the lyrics and speeches, watch a few Spike Lee Joints with an open mind and accept that there is often a disconnect between white and black America. Police brutality and racism against blacks isn’t a fabrication or exaggeration. It’s real.

It’s so real that recently I’ve been uncomfortable not only around police officers but also in a room full of white people. I’m constantly wondering if they’re racist or if I’m acting too black, or I feel like I have to prove how smart I am because I’ve been convinced that all white people think black people are dumb. A few days after Alton Sterling and Philandro Castile were shot and killed, I sent a long message to my nephews to let them know that their lives have value no matter who they become, what style of clothes they wear, what car they drive, who they marry, how much money they have, no matter their career, where they live, how educated they are or how many white people they know.

I’ve heard so many times that students do not feel comfortable discussing race or they’re afraid they might offend someone, so they sit quietly as if these black lives don’t matter. Opal Tometi, a co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement, talked about the dangers of silence during these times.

“We can’t tolerate your frailty. We literally have black boys dying because of your frailty and your inability to deal with the facts,” she said.

This isn’t a black problem. This is our problem, and although a white American may never fully understand what it’s like being an African American, empathy is the next best thing. I don’t want sympathy for black people, and I don’t want to speed through a black rights conversation because people are afraid to voice their thoughts. I want people to imagine losing a child, a brother, sister, uncle, a friend or even a dog just because of what they look like.

Imagine feeling helpless because the judicial system unfairly sentenced the killer of your black family member. Imagine being a young child and watching your father be shot and take his final breath. Imagine being discriminated against at your job or followed by a store employee while you shop for a pair of jeans. Imagine feeling like you would be more attractive or accepted if you didn’t have kinky hair or brown skin. Imagine being black and feeling like your life doesn’t matter.

I was naïve to racism until it stared me in the face three years ago. Writing this today, I realize and find it difficult to accept that I’m a black woman and my life doesn’t matter. I want to have hope in equality, but it’s difficult when mothers, fathers and children are left to pick up the pieces without answers. No matter how hard America tries to convince me that we are post-racism, I know where I stand and how I am perceived in this country. I refuse to be naïve and fall into the “All Lives Matter” trap because I know racism will never die.