Students study obscure phylum

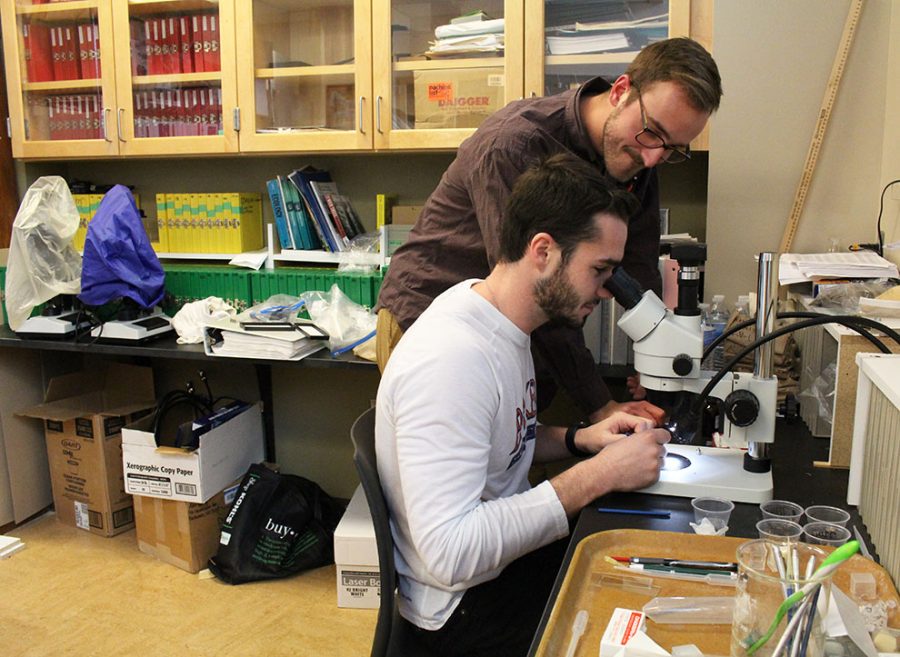

Juniors Cole Stallard and Jake Moore examine slides of different tardigrade species in the Tardigrade Lab inside the Boyd Center on Feb. 6.

The Baker University biology program and a few of its students have been hard at work in the lab and in the field helping lead tardigrade research efforts. Tardigrades are a branch of microscopic phylum which have been studied very little.

Director of Research William Randy Miller is one of the Baker faculty members helping students with their research and is a leader in the world of tardigrade research outside of his involvement with Baker.

Miller recently returned from a trip to Malaysia where he and other scientists went to the island of Panay in the Philippines to participate in a “BioBlitz” of a proposed world heritage site park.

“There were about 50 of us that spent two weeks identifying more than 1,700 animals and plant species in the park area,” Miller said.

Miller has been researching tardigrades for more than 50 years and teaching for 15 years. While he was working with the tardigrades of Australia and the Antarctic, Miller received his Ph.D.

Tardigrades are little known, studied or understood, and they have survived all five major extinctions.

“It is what we call ecdysozoa,” Miller said. “It is an animal that sheds its cuticle.”

Miller said what makes tardigrades so interesting is their ability to survive in a variety of extreme conditions. Some tardigrades have something called the “glass gene,” which allows them to perform “cryptobiosis.” Cryptobiosis is a process that allows them to become dormant and completely inactive, but then when reintroduced to water, some will become active again. When exposed to extreme temperature, vacuum or other extremes, some species are able to perform cryptobiosis.

Due to the animals’ microscopic size and its soft-bodied nature, there is no fossil record to follow. Today’s researchers must use what they can discover now to look into the past.

Miller has brought his knowledge of tardigrades and his knack for acquiring grants from the National Science Foundation to the Baker biology program.

“We’ve managed to pull down a little over $2 million worth of National Science Foundation grants and money,” Miller said.

The grants are not for tardigrade research but are used to help teach students how to do research using tardigrades. These grants have helped fund the experimental design course for biology majors.

Two of Baker’s undergraduate biology majors, juniors Colton Stallard and Jake Moore, are working with Miller to discover new species of tardigrades and identify trends in their populations across the United States.

The experimental design course, or BI298, allows students to develop a thesis and an experiment that they complete and perform over the course of the semester. The topic of the course depends on the subject and the student’s preferences. It gives them the opportunity to lead their own research.

Stallard is a part of the course and has spent the semester working with tardigrade DNA and genetics research. Stallard said the class gives students experience and a chance to publish their work.

Being published as an undergrad is an honor in the scientific community and can help students with internship, graduate and medical school applications.

Miller helps lead the young researchers in the Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU). Moore was a part of the 2017 REU. Miller and a group of other undergraduates from around the country traveled the United States and took samples of lichen and moss from a variety of areas. The group presented their findings in Overland Park and California.

While there is no current application for tardigrade research, Moore believes there is a future for the field.

“I personally can’t wait until we are able to apply the stage of survival to human organs for transplants that way we can save the organs for longer,” Moore said.

Both students will continue to conduct research this semester.

Lily Stephens is a senior public relations major. She has a passion for reporting and creating. Currently she is the Video Producer for the Baker Orange...